Michael Dittman

On Halloween’s Eve 2018, I watched as workers felled a giant oak across the street from my house. When I moved to this small city outside of Pittsburgh, I had been told that this tree marked the grave of Sam Mohawk. Mohawk was a man who, suffering from hallucinations and delirium, killed a mother and her five children in 1843. When he was apprehended, he was standing in a farmhouse playing a fiddle. He was quickly convicted and hanged; no cemetery would take his body, so he was buried in a deserted spot that eventually became my neighborhood.

As I watched that tree fall, I thought, “Huh, that seems like a terrible idea at the worst possible time of the year.” I scratched the scene into my idea notebook.

The next winter, I was very ill. Major surgery left me in bed for eight weeks. During those painful long days and nights, wracked with nausea and staring at the ceiling, I flipped through my idea notebooks to that image of the tree and began to flesh out a story that would become my new novel Who Holds The Devil.

A notebook to capture ideas while they are immediate and fresh is a vital tool for a writer.

Be A Spy

People speak in odd ways. While many writers, native and otherwise, feel the best way to capture the language of Western Pennsylvania is to throw in a few “yinz” and “gumbands”, in reality, capturing the real speech of people is a difficult task.

My notebooks are filled with transcriptions of discussions overheard in coffee shops and classrooms, churches and bars. Sometimes I’m just trying to capture a turn of phrase or a verbal tic; other times it’s an entire story. These elements then turn up in short stories and novels.

Wait, you’re thinking, isn’t that eavesdropping? Yes, yes it is. Remember the wisdom of Harriet The Spy: “. . . if I was going to be a writer, I better write down everything. So I’m a spy that writes down everything.”

Capture Images like a Photographer

We live in an overwhelmingly visual society. Capturing and effectively describing those images can help a writer to create a world or simply to provide inspiration.

Sitting in the Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh, I was drawn to a tiny room behind an open, but unmarked door. I went in and spent a few minutes recording the layout and contents, imagining where the locked door on the far wall could lead.

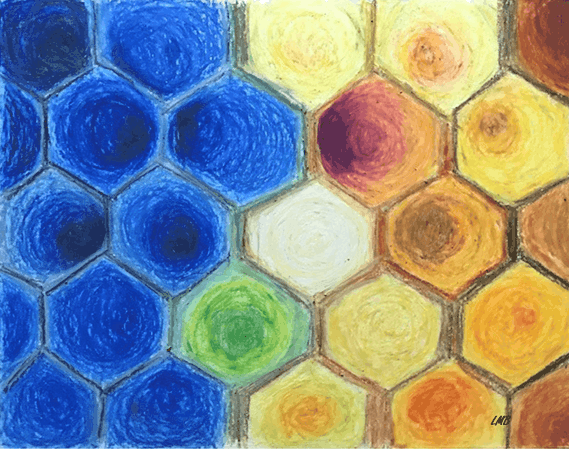

Walking through the Cleveland Museum of Art, I came across Anselm Kiefer’s painting “Lot’s Wife”: a huge image of a burnt apocalyptic landscape slashed with thick layers of oil paint and embedded with ash and copper. I stood in front of the art scribbling furiously in my pocket notebook trying to capture both the physicality of the piece and the way the image swirled and bled.

Making my way into an Eat ’n Park, I moved past a table of old men dressed in variations on a theme: cheap ballcaps, short sleeve dress shirts, and suspenders. I spent a moment sitting over coffee and describing them in sharp detail.

All of these images show up in Who Holds The Devil. Not verbatim, but as models both physical and emotional. The job of the writer isn’t, after all, to copy reality, but to improve upon it.

Capture Your Dreams (Or Nightmares)

Bear with me here; I’m not proposing an Oprah-style visualization manifestational notebook.

I have sleep paralysis. On top of that, about six days out of the week, I am plagued by nightmares. My notebook sits beside the bed and as I struggle awake, I hurriedly capture them.

You may have sweeter dreams, but they are all rich sources of inspiration. Our minds are hindered by reality and by an internal editor that tells us that some ideas are too fanciful or distasteful. Our subconscious is unencumbered by that voice (I think here of Edward G. Robinson in Double Indemnity talking about the “Little Man’ in his gut that keeps him up at night), but our dreams, good and bad, captured in a notebook can provide endless scenarios and details that provide new ways of writing about our world.