review by Karen Weyant

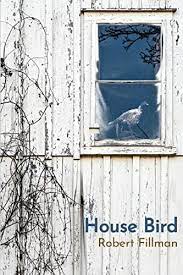

Many years ago, I discovered Robert Fillman’s poems in the literary journal Rust+Moth, and I have been following his work ever since. When I finished reading his debut full-length collection of poetry, House Bird, I realized what it was that made me admire his work so much: every line and image seeks to find meaning in what gets remembered and told and what is almost (but not quite) forgotten. In essence, in Fillman’s poetry, memories become art.

Fillman starts off his collection with a poem “Cleaning out the basement closet” where a narrator finds a discarded deck of “dirty playing cards/from a friend’s bachelor party” and is instantly traveled back through memory to his grandfather’s coal cellar and a poster of a “beautiful woman, half nude/hidden from my grandmother’s view.” Already, we get a hint of Fillman’s poetic voice and style as we witness both an engaging narrative with the understanding that the forbidden objects found in this poem represent those stories in our family histories that we rarely speak about or void talking about at all.

In the pages that follow, the reader will navigate a life of these histories. Some of these memories are clearly from childhood. For instance, in “When Kurt Cobain Killed Himself” a mother wrestles with how to give the news of a favorite icon’s death to a son who was “a sheltered child” and who had “never even been/to a funeral, or helped/his dad bury a dead pet.” In other poems, however, Fillman portrays a narrator looking at life as an adult. In “Toast” he muses over his own secrets as he makes breakfast for his children, tearing a slice of bread slightly with knife, and in “Cicadas” the narrator describes the insects’ rattling as “a chorus curls up from within/the tree line, rising and getting/ sharper, a yellow fluttering/sound” while contemplating the fact that to admire such music is also to admit that summer may be drawing to a close.

But perhaps my favorite poems are the ones where Fillman navigates the adult world with memories of the past. Indeed, there is one poem where I turn to again and again as it illustrates the complexities of the contemporary elegy. In “Elegy for My Cousin Laura” the narrator walks past his cousin’s house and remembers the days that they played with the Ouija board as children. He admits that this was child’s play but also realizes that “as children we believed/that we could cross into that/forbidden realm where the dead/listen for their names, failing/to realize then that one day/we’d be on the other side.” It’s this realization, that they were playing with mortality even as children, that makes the narrator mourn the loss even more and perhaps think about his time here on earth.

In essence, House Bird is a fine debut. It is a stellar celebration of memory in all of its many poetic forms. Somehow, Fillman manages to avoid nostalgia, even when he tackles subjects that would easily fall into the trap of sentimentality. This is a book that I will be reading over and over again, and indeed, I am looking forward to Fillman’s future work.